It’s a truism in architecture that new ideas proceed from constraints on the designer’s imagination, like an oddly-shaped site or tougher energy requirements. But what happens when the constraint is an economic crisis gripping an entire nation?

In Greece, which has been squeezed by debt, recession, and austerity for nearly a decade, finding work has been even more difficult than usual for a generation of young architects. Yet Konstantinos Pantazis and Marianna Rentzou of the Athens-based studio Point Supreme have managed to forge unconventional new ways to design their way through the crisis.

Pantazis and Rentzou founded Point Supreme in 2008, after studying abroad and working at global practices like MVRDV and OMA. Like Portugal's Fala Atelier and the Netherlands’ OFFICE Kersten Geers David van Severen, the duo has gained international recognition for carefully balanced architectural collages charged with historical references and a colorful palette that carries through into their built work.

If architectural collage is often perceived as pure visual abundance, Point Supreme’s work shows a thoughtful composition of color and texture that reflects the spirit of Athens’ historic streets and structures. Representing their environment in two dimensions, Pantazis and Rentzou have developed a fine-grained feel for the existing city while assembling new spatial narratives that speculate on the Athens of a post-austerity future.

The architects’ Petralona House exemplifies the firm’s economical, yet exuberant design process. Anchored in the social and historical context of their home city, the house borrows elements from the rich cultural texture of Athens to build new histories through new architecture and material analysis. Each space invites a different story and context: a utilitarian kitchen connected to a garden, a sculptural staircase leading up to a ‘Japanese room,’ a Corbusian cantilevered mezzanine, and so on.

In order to build out the individual narratives of the house’s rooms and spaces, the architects gathered an array of hand-made, found or gifted objects and materials into the fabric of the home: Rentzou’s father, a skilled metal worker, hand-made the steel staircase, while material donations from manufacturers like Tsourlakis, Hager and Legrand, Grohe and Vitruvit provided cement floor tiles, plugs and bathroom pieces, respectively. In the context of the crisis, with Greece’s public sector facing collapse, the assemblage technique feels like an assertion of resourceful cooperation.

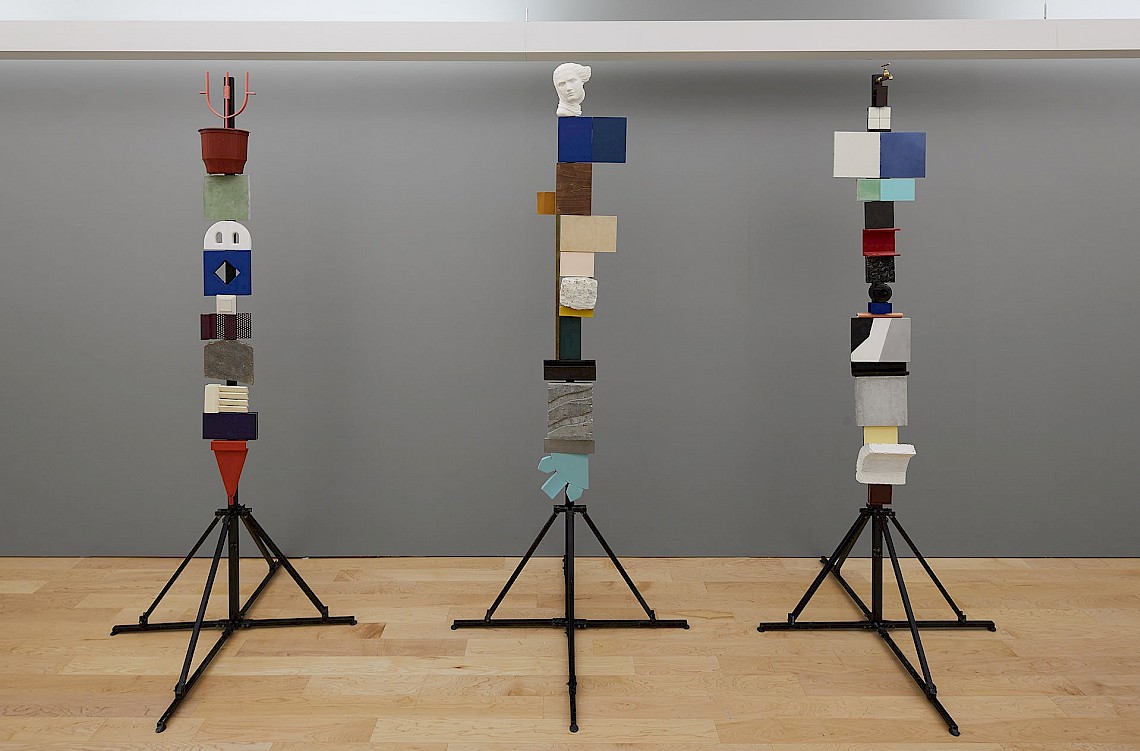

Point Supreme’s installation at the Chicago Biennial is an intimate meditation on that gradual process, which neatly addressed the Artistic Director’s mission to “Make New History.” The architects’ installation interprets the bricolaged home not only as an economical response to the circumstances of building in a Greece very much held back by a weighty recession, but also nods to local craftsmanship and architectural history. The presentation is made up of two parts: Totems and the History Wall. Totems, pictured below, consists of three poles, on which samples of the materials used in the house figure.

At the Biennial, the house’s materials are arranged on the poles in a linear fashion, with one pole attributed to one area of the house: exterior, ground floor and top. Deep blue tiles, dark grey stone fragments, and accents of ochre, burgundy and aquamarine sit on the poles like three human figures parading a cubic assortment of accessories.

The arrangement presents the visitor with an idea of the way the architects were themselves presented with available resources to work with. On the poles, the architects have eliminated all hierarchy from their material palette, presenting each piece with equal weight and letting the visitor imagine their corresponding placement in the built work. The artificial, the market-produced, the handmade, the new or reclaimed, original or copied, Greek or imported, all coexist with no specific value, price or purpose.

Directly opposite from Totems in the gallery, the History Wall is a collaborative project with artist Nikos Magouliotis, which presents photographs of the completed Petralona House side by side with a selection of reference images, situating the home in relation to the full sweep of Greek architecture, art and history. Athens street scenes and cavernous entrances mirror the smooth walls and curves of the Petralona House, while a vessel with painted figures recalls the mural on the cantilevered top floor of the house.

At a time when Greece is struggling to regain its economic footing in Europe, the architects have built themselves a new home with materials already available — giving those fragments of Greek history a new purpose. The final product is a celebration of the country’s rich creative heritage in the form of bricolage, where accumulated materials coming from different parts of the city are brought together to build a contemporary space.

“For us to ‘Make New History’ is to combine different histories, without prejudice,” said Pantazis and Rentzou. Weaving Greek heritage with the story of materials in the Petralona House, and the story of their own home, designed and built for a growing family, the architects explore the extent to which a single project can be interpreted through history. At one end of the spectrum, the house may seem like a well-curated collage, brought to life through accessible and local materials at hand. On the other, the initial collage is a patchwork of cultural references to Greece’s creative heritage, drawing from Hellenistic art and local architectural forms, colors and materials.

This is the second year that Point Supreme is participating in the Chicago Architecture Biennial. In their 2015 exhibition, the architects placed collages of urban proposals for Athens side by side with photographs of their realized buildings, drawing connections between the ways spatial narratives are conveyed in each format.

“In this year’s installation,” explained the firm, “it was clear to us from the beginning that we had to have a physical presence [at the Biennial],” that responded to the architecture of the Chicago Cultural Center. Therefore, Totems does not merely act as a model for the material palette of the Petralona House, it also acts as a material representative for the house.

Originally conceived for the Pavillon de l'Arsenal's "30 architectes" exhibition in Paris, Totems behaves as a vessel for the architects’ personal home, transporting it from city to city as if bringing a small piece of Athens to each new site. The process is a means for the architects to reflect on their own work “and how it relates to the work of [their] contemporaries,” but also to expand on the symbolic significance of Greek heritage in their architecture. Participating in survey exhibitions like the Biennial, explain the architects, allows Point Supreme to “establish a sense of belonging,” which counteracts with the practice’s own operating context at the edge of Europe.

Currently, Point Supreme is working on international collaborations with offices outside of Greece, and will be directing a studio next semester at Columbia University’s GSAPP.

Explore more projects by Point Supreme in the Chicago Architecture Biennial’s Are.na channel below: