This past summer the Chicago Architecture Biennial launched this blog with an inaugural “Directors’ Note" from me. I’m proud of how this digital space has, since that time, extended the mission of the Biennial as a civic-rooted platform for the field of architecture beyond the geographical confines of Chicago and its region, including varied perspectives from around the globe. I’m back today on the CAB Blog to share some reflections about what we’ve accomplished so far, using the ideas I floated here in June as a yardstick.

We are fully into autumn now, the public opening of the Biennial on September 16 is one month behind us, and on Tuesday I marked my first full year leading the Biennial as its Executive Director. The Biennial’s most significant impact in my mind remains the opportunity we have to include a more diverse public in advanced dialogues about how the field of architecture best attends to the transformation of this shared world.

Over the last four weeks, we’ve begun to assess what it means to bring the themes being unpacked in “Make New History” to this broad public. Architecture is all around us, and we should expect it be an accessible cultural field. But talk about architecture tends to be insular and fragmented, with distinct subcategories (call them “discourses”) dividing, for example, professionals from small start-ups from large corporate practices. Similarly, academic historians aren’t always at the same table as scholarly practitioners, and the followers of social media critics typically diverge from the audiences of big city journalists. Allied professionals working in development, planning, or preservation have their own unique patois and forums to match.

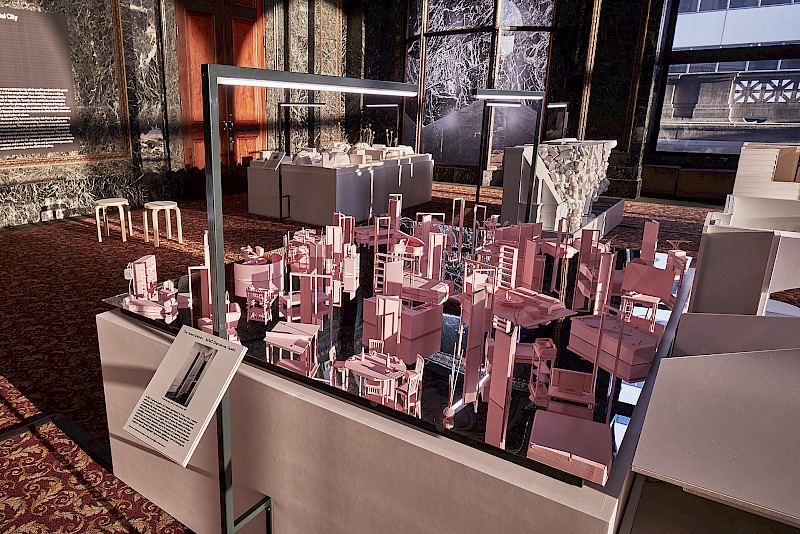

The Biennial provides a means to focus these divergent strains of architectural thinking and make them accessible through a cultural lens united around a singular theme. This second edition, under the Artistic Direction of Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee, makes the current debates about what’s most important to the built environment palpable by emphasizing familiar and fundamental techniques that unite the architect and the childlike impulses in all of us. The large models, mock-ups, peephole interiors, and soaring arcades aren’t dollhouses, toy train sets, or dioramas, but they welcome the same kind of curiosity, enjoyment, imagination, and sense of play. They also suggest the innate desire to probe and ask questions.

The public response to these attractive yet provocative aspects of the exhibitions has been remarkable. We greeted 31,000 visitors during the first four days of press, professional previews, and the public opening weekend. This inclusive public was engaged across multiple Biennial sites, with the Chicago Cultural Center hub joined by the City Gallery at the Historic Water Tower, Garfield Park Conservatory, Community Anchors in six distinct neighborhoods outside of the city core, and special performances at the Navy Pier and Farnsworth House. Since then we’re tracking close to 16,500 visitors each week at the Cultural Center. We will continue to measure the expanded impacts on neighborhoods as we engage community residents close to home and invite visiting audiences to expand their itineraries beyond the city core.

But invitation isn’t enough. Certainly there’s a great deal of joy as folks play with and share our various “Supermodels” (both Vertical and Horizontal) on Instagram; arrange meetings at (or somersault upon) Frida Escobedo’s monolithic timber platform Randolph Square; attempt hide-and-seek in the AGENdA, Camilo Echavarría, and Camilo Echeverri-designed curtains of MIES Understandings; or duck in to see fantastical chapel scenes envisioned by baukuh and Stefano Graziani between the Queen of Sheba and an Italian industrialist. The Biennial is also challenging architectural audiences to become participants who are also scrutinizing and considering what "Make New History" means today. That is to say: why is history an urgent topic for provoking a more accessible public conversation about architecture?

The 2017 theme pushes back against a popular tendency to consider concepts like “progress” or “innovation” (the “shiny new”) at odds with concepts like “precedent” and “history” (the “dusty old”). David Schalliol’s documentation of the untimely fate of Chicago’s public housing and Aires Mateus’ poetic videoscape Ruin in Time meditate on “progressive” architectural ruin overtaken by the longer timeframe of geological and natural time. Among other projects, both demonstrate viscerally how a certain sloppiness of thinking that devalues history in the name of progress has devastated our planet and shared civic realms.

On the other hand, capital H-history is invariably associated with didactic approaches and an overvaluation of global expertise over other forms of knowledge. Learning implies classrooms lorded over by folks who know better. It is no wonder people eventually put history along with education in the rear view mirror and focused instead on the seemingly more practical tasks of inhabiting and making the world.

This edition of the Biennial challenges the notion that we ever “get over” history. It shifts the question from passive reception of knowledge to active learning and a continuous process of analysis and critical observation. It suggests that every act of making “new” ought to lend careful consideration to what’s already been done. To me, these ideas are connecting to what’s urgent and are a powerful antidote in an era defined by splintered interests and a proliferation of screen-mediated distractions that fragment the potential for collective action.

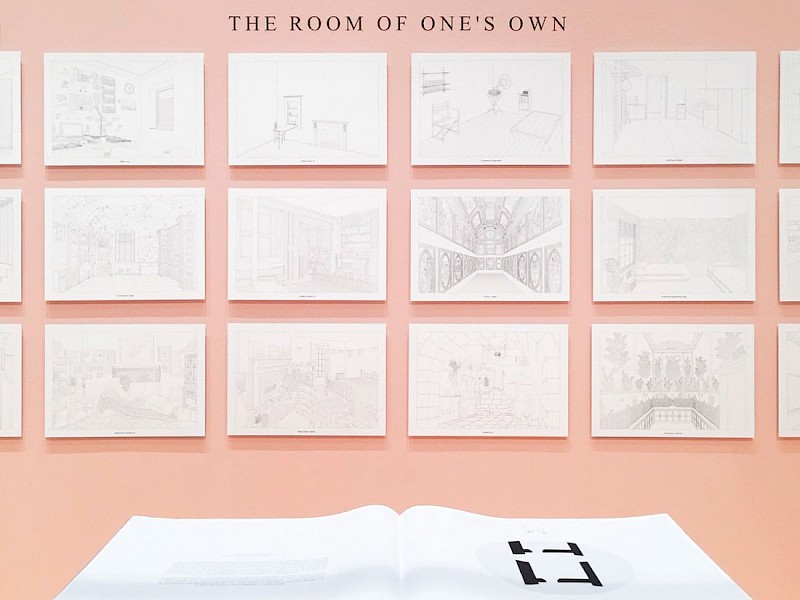

Indeed, Brussels-based Biennial participants Dogma quote feminist 19th-century author Virginia Woolf while presenting a multitude of “rooms of one’s own”—not as privatized spaces on our cellphones, but as a fundamental condition of identity formation through concentration and reflection. Their project, Rooms, envisions the intellectual space of figures as varied as Mies’ overlooked collaborator Lilly Reich and innovators working on the imagination and unconscious through art (Frida Kahlo) and science (Sigmund Freud). Quite a number of participant projects demonstrate this spirit of rigor and persistent observation over time, whether revisiting in granular detail Haussmann’s influential plan for Paris or analyzing more sustainable and equitable ecological profiles of Chicago’s iconic Loop towers.

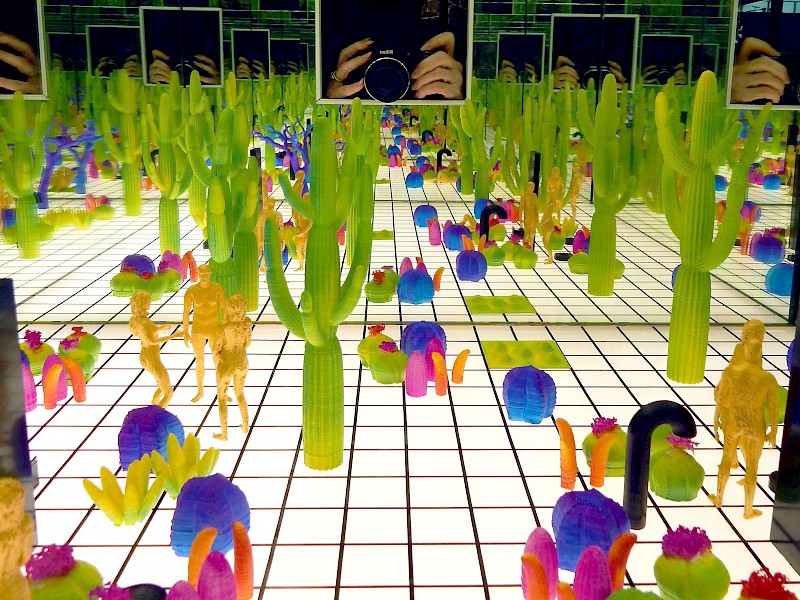

Play and imagination are also part of this spirit of learning-infused projects. UrbanLab’s exuberant, Superstudio-inspired A Room Enclosed by Hills and Mountains all but compels visitors to take infinity mirror selfies—but the architects also bring a new generation into a conversation about our connected world that originally emerged from the convergence of the Italian avant-garde and anti-establishment American hippies in the early 1970s.

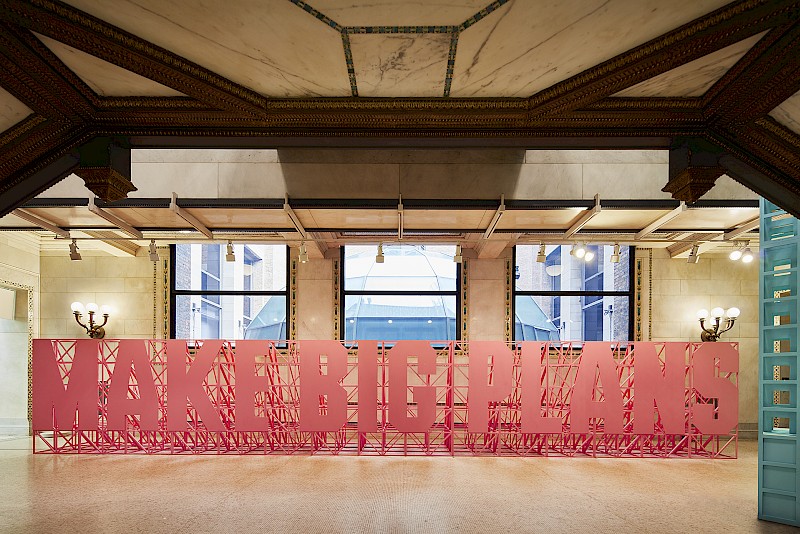

We also saw the potential for students and citizens from outside architecture to work with experts and professionals across generations and cultures to co-create and collaborate. Pritzker Prize winners SANAA teamed up with Chicago’s Illinois Institute of Technology to imagine how Bronzeville could be reconnected to the lakefront. Ohio State University’s Knowlton School of Architecture team paired with Rotterdam’s Monadnock to recast Daniel Burnham’s mantra "Make No Little Plans" as a temporary monument that both celebrates and questions this declaration of bigness in complex times. In this same vein, traditions of art and culture from Arizona’s Tohono O’odham Nation, Senegalese Tambacounda regional thatched roof construction, and local building practices in India inform architecture in collaboratively-defined participant projects by Aranda Lasch and Terrol Dew Johnson, Toshiko Mori, and Studio Mumbai.

Often it is our expanded team that notices these details, acting as intermediaries between the participant projects and the public. The staff on site is crucial to helping us understand how people are responding to and interacting with these 141 projects representing more than 25 nations. Every day of our “Biennial operations” is made possible by a distributed nerve center of 141 active volunteers who comprise our team “on the floor” of the Cultural Center, serving as greeters and providing free guided tours customized to their perspectives.

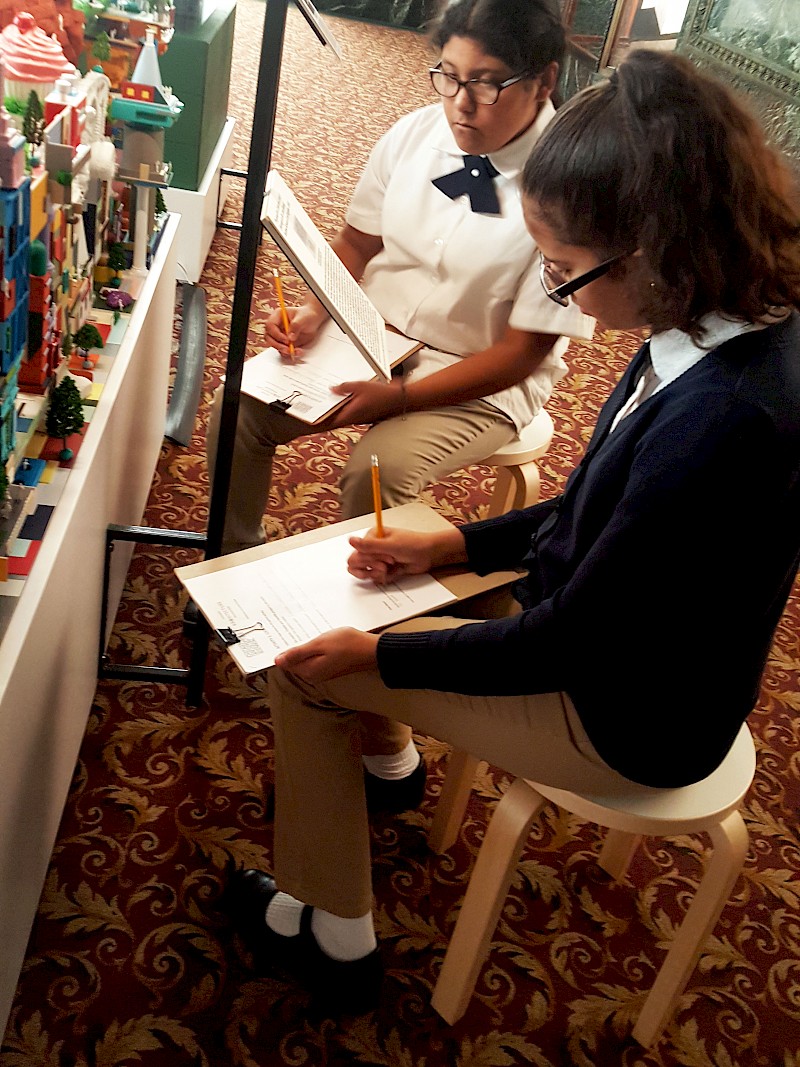

Supporting all of these goals depends on our core team, and I am personally grateful to (and proud of) their commitment to the Biennial. Starting from a rather humble beginning, we’ve grown to a staff of fourteen (all listed on our website), who ensure that our communications, public programs, partnerships, and visitor experience are aligned. When I started this job on October 17 last year, Rachel Kaplan the Biennial’s returning Manager of Productions and Exhibitions and I shared a cubicle in the planning office of our presenting partner and host, the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE). We couldn’t have ramped up to the successes we’ve charted without the continued support of everyone at DCASE, from the Commissioner Mark Kelly to the visitor experience, events, and security team. Together we have worked closely with our Signature Education Partner, the Chicago Architecture Foundation, who have made 82 Chicago teachers participating in their professional development workshops ambassadors of these projects. They’ve helped register 52 schools to date for field trips that take the exhibits as the catalyst for a participatory curriculum.

We consider the 254 programs on the calendar and 24 partner exhibitions across Chicago as both essential to and continuous with the dialogue that begins in the Cultural Center. More than 70 diverse programs have already been held, running the gamut from tours and exhibitions to lectures, workshops, and screenings. Some have offered fresh reflections on well-recognized subjects like the Bauhaus or Frank Lloyd Wright, while others open up architectural discussions to consider lesser-known contributors. We’ve also seen works that tackle urgent matters like global pollution and the persistent barriers of race, gender, and sexuality through the lens of history and other creative forms, including film and performance.

Acting collectively, we reach for the powerful possibility that an accessible and expansive architectural field can be galvanized to find solutions to our most urgent needs. Having a shared historical perspective becomes an essential civic tool we wield together, whether to consider the critical infrastructures undone by climate change in Puerto Rico, reconsider the fragile coexistence of building and nature in Mexico and Northern California, or revisit the legacies of historical values ascribed to the poor when building homes in London or Chicago. Through models and play, we hope to unlock new solutions in young minds.

We’ve seen it happen just this last month on the Near West Side at the National Museum of Mexican Art Community Anchor Site, which collaborated with undergraduate students from Tecnológico de Monterrey in Querétaro to recreate a work by Oaxacan art activist Francisco Toledo. The students held a workshop to make kites that briefly resurrected lost or threatened murals, underscoring themes of the anchor exhibit documenting Pilsen’s historic but vulnerable built heritage.

On the South Side at the former Anthony Overton Elementary School in Bronzeville, Opening Closings, organized by architect Paola Aguirre’s Borderless Studio and the Chicago chapter of DOCOMOMO, inaugurated our “Connector Projects” underwritten by the Field Foundation. In the ruins of a progressive example of school design by firm Perkins + Will, high school students led by Phil Cotton and Chicago Arts Partnerships in Education transformed the decommissioned site. The event turned adult attendees back into students and the students into teachers. The high schoolers shared novel ideas, ranging from reuse of the decommissioned school structure to art installation prompts for addressing the future of public education.

Over the next months—through the closing of the core exhibition on January 7—we will continue to learn from the insights and perspectives expressed by communities across the city and visitors from around the world. As this public demonstrates new ways of engaging the legacies of our built environments, we will discover where CAB goes next.