Some works of architectural writing can be taken at face value as stark manifestos for a new aesthetic. Keith Krumwiede’s Atlas of Another America is, instead, a constantly unfurling satire that offers layers upon layers of artfully imagined social commentary. Like McMansion Hell, my own long-form satirical project, Krumwiede’s “architectural fiction" sends up American ideas about economics, politics, and culture by picking apart our outrageous suburban housing types. The project will be on display at the Chicago Architecture Biennial this fall, delivering a sardonic vision of American architecture that comes out of academic theory, but has a potent message for anyone who has spent time in suburbia.

Krumwiede’s book parodies the form of an 18th century treatise in order to propose a tongue-in-cheek vision for the suburban landscape of the United States after the 2008 financial crisis. Named Freedomland, this new utopia borrows town planning ideas from Thomas Jefferson’s plan for parceling the nation’s land in a grid system—the idea that created the patchwork of farms, streets, and small towns recognizable today.

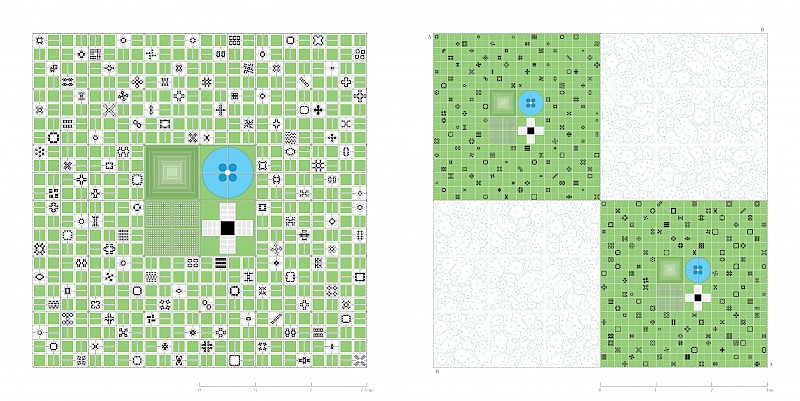

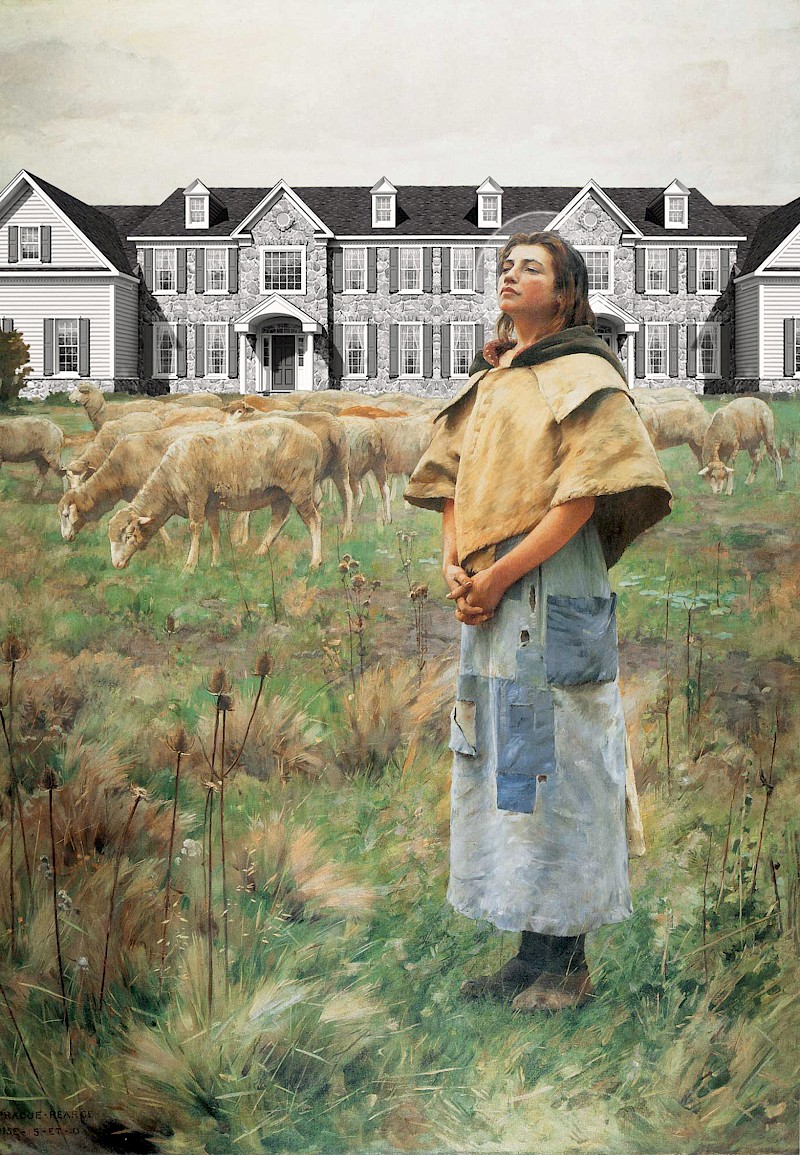

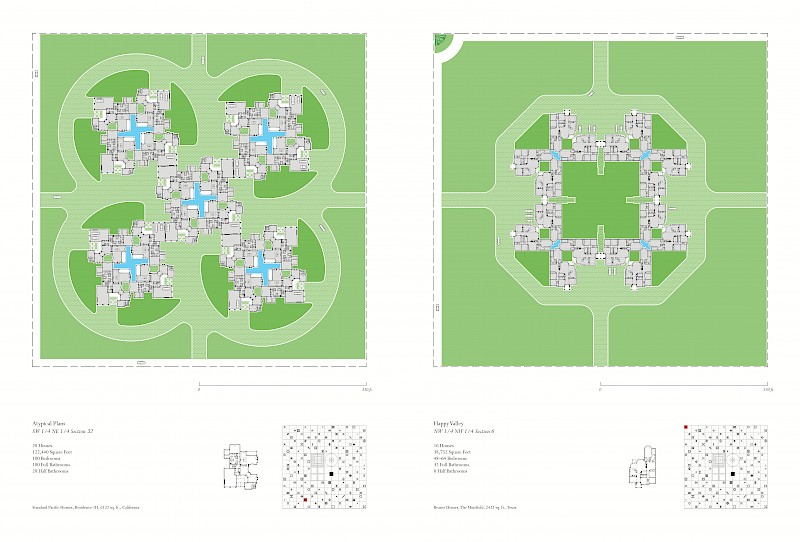

Detached suburban houses are out in this brave new world. Instead, everyone lives together inside sprawling estates based on plans the author borrowed from actual McMansions, then stitched together and mirrored, inverted, or otherwise organized into massive, fractal compounds. The book pairs a collection of these plans with extremely amusing collages in which these Franken-mansions invade the backgrounds of bucolic European paintings.

Krumwiede’s caricature of unhinged suburbanization may seem far-fetched, but it lays bare a set of very real forces driving inequality across the American landscape. In a simultaneous nod to both manifest destiny and suburban sprawl, for example, the only limits to Freedomland’s expansion are “geographical or political obstacles”. He calls out America’s increasingly hostile attitude toward public education. Freedomland does not allocate land for schools because “the choices in means and methods of education are best left to individual families.”

Freedomland also takes the the racial and aesthetic homogeny at the heart of American suburbs to new depths. Its gloomy twist on the homeowners’ association covenant dictates that each “particular estate [is] one just like the next...ensuring cohesiveness of identity and consistency of character such that property values...and community values are promoted.” Just like in the real world that I document through McMansion Hell, the design for each mega-development is “carefully selected from among the best produced by the country’s greatest builders” (a.k.a. speculative developers). Krumwiede takes on the failure of architects to provide for the community, finding them to be “disinclined, or perhaps just ill prepared, to deliver designs desired by a majority of the American people…”

The fake architecture of Freedomland visualizes the neoliberal landscape of the late 20th century taken to its logical extreme. If McMansions and their ilk epitomize what President George W. Bush called “the ownership society,” then Freedomland asks what comes next when the market crashes. Its improbable mashup of ideas from across the political spectrum and American history—which forces yeoman farmers into collectivized housing projects—is really a way of asking how Americans will ever resolve the wicked problems firmly entrenched in our built environment.

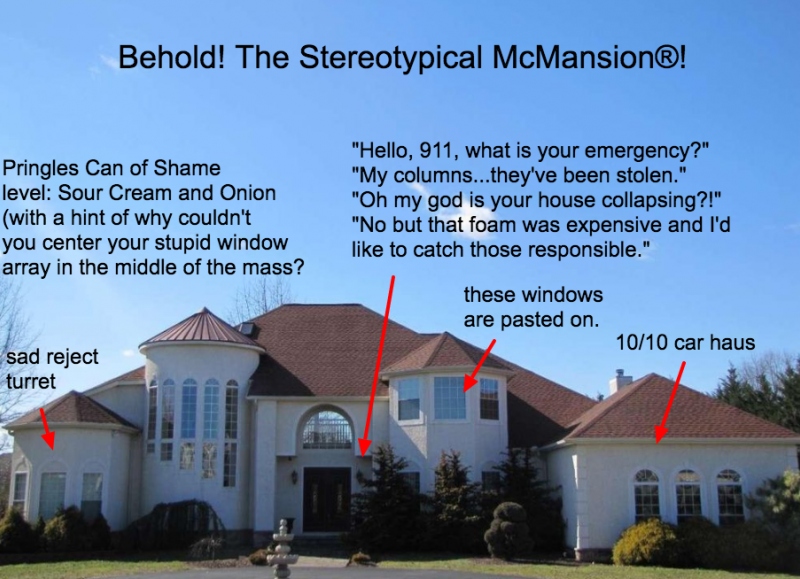

Krumwiede attacks these issues from a theoretical vantage point as a designer and scholar. Whereas he draws on history and fiction, my own perspective is much closer to reality: McMansion Hell draws on listings from online real estate directories like Zillow to critique the terrifying “McMansionization” of American exurbs in real time.

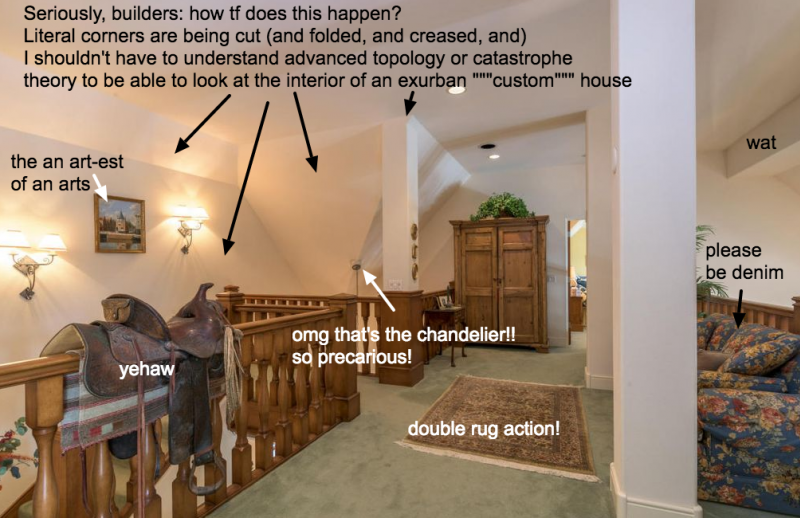

But both projects try to glean insights about contemporary society by minutely describing the texture of its monstrous creations: the sadly empty “lawyer foyers,” the infinite shades of beige, the standardized ceiling heights, and the inexorable desire for bigger and better status symbols. And both projects package nuanced ideas in ways that general audiences can quickly grasp. Visitors to the Biennial will recognize the quirks and faults of their own communities in each absurd illustration of Freedomland.

Like Krumwiede, I’ve found that these artifacts are easier to talk about than the enormously complex roots of the financial crisis itself. While McMansions didn’t cause the crash, for example, they are fitting symbols of the dubious financial products and hyperinflated markets that did. They employ the architectural symbols of wealth without having the substance of actual durability.

They also make surprisingly poignant images for the same reason. It’s no surprise that Krumwiede places these alienating domestic spaces in the same category as “greeting card poetry” and “serial television,” which provide a repetitive and generic backdrop for modern life. But he also empathizes with the real people who inhabit these surreal spaces. In a way near and dear to my heart, Krumwiede touches on the “non-utilitarian” desires of those who build enormous houses, from “oversized columns” to “coffered ceilings” and “artfully staged furniture.”

One of the original goals of McMansion Hell was to get people interested in understanding how their own built environment turned into this suburban wasteland. I was hoping to start a larger conversation about design, real estate, and inequality by first poking fun at some truly insane houses. I was also interested in breaking down architectural theory, which can be rather dull at first, so that it actually had something meaningful to say about the suburban landscape for an online audience. Using the visual language of memes, McMansionHell introduced a series on “architectural theory for the rest of us” beginning with Vitruvius. McMansion Hell’s weekly house roasts frequently allude to works by contemporary theorists like Rem Koolhaas and Greg Lynn, not just by making jokes at their expense, but also by recontextualizing their work using text-based annotation.

In the eyes of my blog, architectural theory doesn’t need to be supercilious and serious all the time. One can find humor in the most academic and dense theoretical ideas—from British Palladianism to deconstructivism—and it’s about time we did. Not only should we make theory humorous, but we should also situate it in the context of our daily lives. That includes the most common American landscape: Suburbia. This is the idea that drives both Atlas and McMansion Hell: architectural theory and criticism should be applied to the “non-architecture” of the suburbs outside of the explicit urbanist directive of “fixing” that landscape. Tone is also key: few people enjoy being talked down to by experts, especially when it comes to the places where they live.

Indeed, the tone of Krumwiede’s book is perhaps its greatest achievement. At times it is openly satirical, and its vision of America shifts between utopia and dystopia, humor and serious commentary. The structure of the book as fictional treatise, collection of plans, deconstructed essay, formally constructed essay, and work of fiction make it both a top-down and bottom-up form of commentary. To one audience it’s a winking meditation on architectural theory. To another it’s a book of physical memes.

Krumwiede’s games with syntax and vocabulary are all unusual in a serious print work, but his creative riffs on established vernaculars and recurring tropes resonate strongly with the mashup culture of memes and online satire. Like a seasoned Redditor, he deconstructs well-known references and reconstructs them in new and absurd ways. Connoisseurs of internet culture will also recognize the mocking self-seriousness of the project’s antiquated language.

The community surrounding McMansion Hell has also evolved its own vocabulary of internet layman’s terms for the architecture of domestic excess. Terms like “nub,” which describes the artifacts of poor roofline planning, and “an art,” denoting corporate, mass produced wall decorations, are proof that regular people can change the conversation around buildings to suit their own perspectives. I often receive emails describing how these McMansion pseudo-memes Hell somehow find their way into the spoken vocabulary of readers, which shows promise in my one-person campaign to bring architecture to the masses. If you can remember something in such a convenient way, you can use that trope to teach others as well.

Freedomland will certainly resonate with the McMansion-hating crowd as a critique of both late capitalism and American architectural and urban planning heritage going back to Jefferson. These aspects coincide with its proposal of new, if satirical, ideas within that ideological framework. It is a critique of the present as perceived through the lens of the past, executed as a plan for an uncertain future. The project’s quirky openness also gives me hope for an expanded conversation about American urbanism, one that makes the complex formulations of theory understandable and accountable to the engagement of a much wider public.

Kate Wagner is a freelance writer, sound engineer and creator of the viral blog McMansion Hell, which roasts the world’s ugliest houses while teaching about architecture and design.

The 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial blog is edited in partnership with Consortia, a creative office developing new frameworks for communication around design. This article also features embedded content from Are.na, an online platform for connecting ideas and building knowledge.