The Tribune Tower has stood at the heart of Chicago’s cultural heritage for almost a hundred years. Like the spire of a secular cathedral, it still symbolizes the rise of the “city of big shoulders” and its defining role in the American Century. But the building is more than a Chicago icon. The story of its origin has proved to be one of the most enduringly influential narratives in 20th Century architecture, key to understanding the skylines of cities all over the world.

A groundbreaking skyscraper was the highest ambition of Colonel Robert R. McCormick, the powerful publisher of the Chicago Tribune and a man who dominated local politics before the First World War. Hoping to project an aura of international prestige for his burgeoning media empire, the competition brief he compiled asked architects to create “the most beautiful office building in the world.”

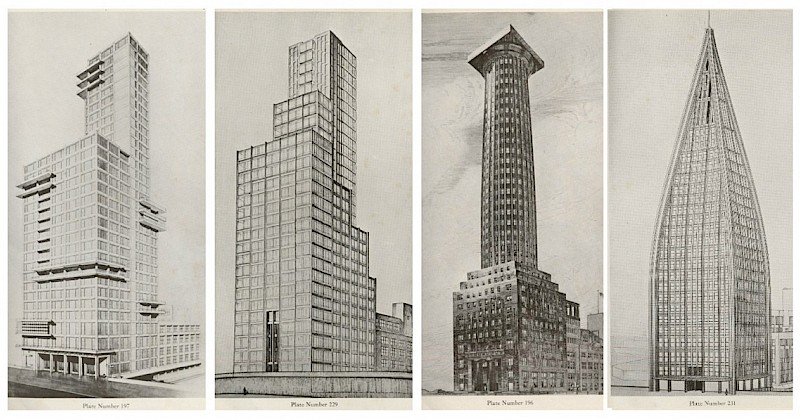

More than 260 architects from 23 countries responded with designs in a dizzying range of styles. Some entries stretched the office tower’s vertical structure into extended Gothic arches with delicate tracery, while others segmented the facade into Neoclassical orders with stepped porticoes and colonnaded temples for crowns. Forward-thinking architects submitted sleeker designs modeled on factory architecture, Chicago’s existing masterpieces, or the angular ornamental motifs that would later be known as Art Deco. Some reduced the building to a single symbol; an arch, an obelisk, a giant Native American figure, or even an enormous billboard spelling out the headlines of the day.

The winners, Raymond Hood and John Mead Howells, proposed the Gothic tower that now graces the corner of Michigan Avenue north of the Chicago River. Their design balanced the vertical spirit of US commerce with Gothic flourishes from French tradition – including a dramatically buttressed crown borrowed from the 13th Century Cathedral in Rouen.

While major international competitions may be a familiar sight in the architectural sphere today, the Tribune Tower competition was unique for its global influence on the future of the field. Audiences could compare and evaluate starkly contrasting ideas from the world’s foremost architects at a glance; the results—published widely—produced a ripple effect which influenced different schools of thought competing to define the look of the “Modern Age”.

Not only did echoes of the design of the winning skyscraper appear throughout the pre-war period, but several other entries resonated with later generations. Eliel Saarinen’s design, a runner up, heavily influenced several North American skyscrapers built as late as the 1990s. A tongue-in-cheek proposal by Austrian architect Adolf Loos to turn the building into an enormous Doric column, playing on the “columns” that compose a newspaper, went on to inspire Postmodernist architects with its readymade look and its playful engagement with language.

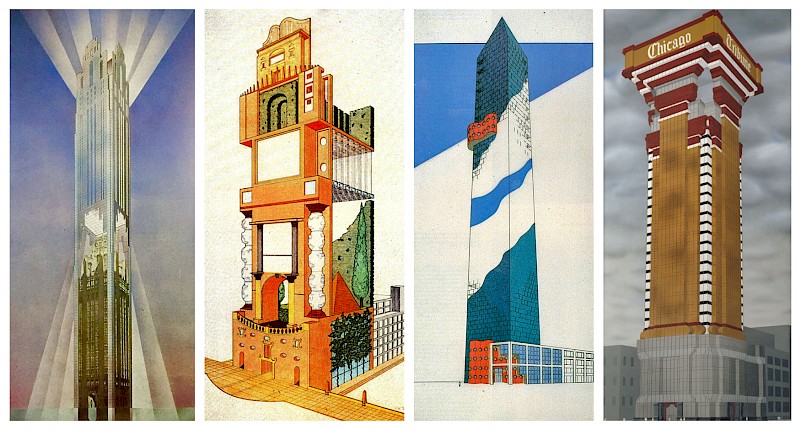

Architects have remained so obsessed with the ideas of the unbuilt Tribune Towers that reimagining the competition has become something of a tradition in its own right. In 1980, the Chicago architect and Postmodern provocateur Stanley Tigerman organized a winking do-over of the original contest. In a volume called Late Entries to the Chicago Tribune Tower Competition, he published the original designs alongside new drawings by the likes of Frank Gehry, Alison and Peter Smithson, Bernard Tschumi, and Tadao Ando.

Some of these designs drew directly on the older source material, like Arquitectonica’s red, white and blue obelisk. Others riffed on the metaphors encoded in the statues, temples, signs and columns that topped earlier designs, replacing them with baby bottles, globes, trees, White Sox uniforms, and giant newspaper pages.

The book even featured a number of architects who would go on to shape the Chicago skyline in vastly different ways: Helmut Jahn, the designer of the Thompson Center, submitted a geometric tower that floated impossibly above the original building. Tod Williams and Billie Tsien contributed a craggy volume perched atop four enormous boulders – prefiguring their monolithic designs for the Logan Center at the University of Chicago (completed in 2012) and the forthcoming Obama Library and Presidential Center.

The “late entries” may have been offbeat, but Tigerman’s goal was to take the temperature of the architecture field during a moment of radical change. Just as Gothic ornament and Bauhaus modernism brushed cheeks during the 1922 competition, these represented a cross-section of contrasting ideas from some of the most radical thinkers of the late 20th Century.

Some of the more opinionated entries came from thinkers whose drawings would motivate new generations of architects to think in new ways about history, tradition, and form. Others would go on to design real skyscrapers that imprinted the visions developed in the contest on the skylines of US cities.

Argentinian-American architect César Pelli, who would become one of the world’s most prolific skyscraper designers, incorporated Postmodern rooflines and decorative elements into buildings like Cleveland’s Key Tower and the Carnegie Hall Tower in New York, but he also built several skyscrapers with the classic step-backs and rectangular proportions of Saarinen’s snubbed design – like the Wells Fargo Center in Minneapolis (1988) and the Bank of America Corporate Center in Charlotte (1992), as well as Chicago’s 180 W. Madison Street (1990).

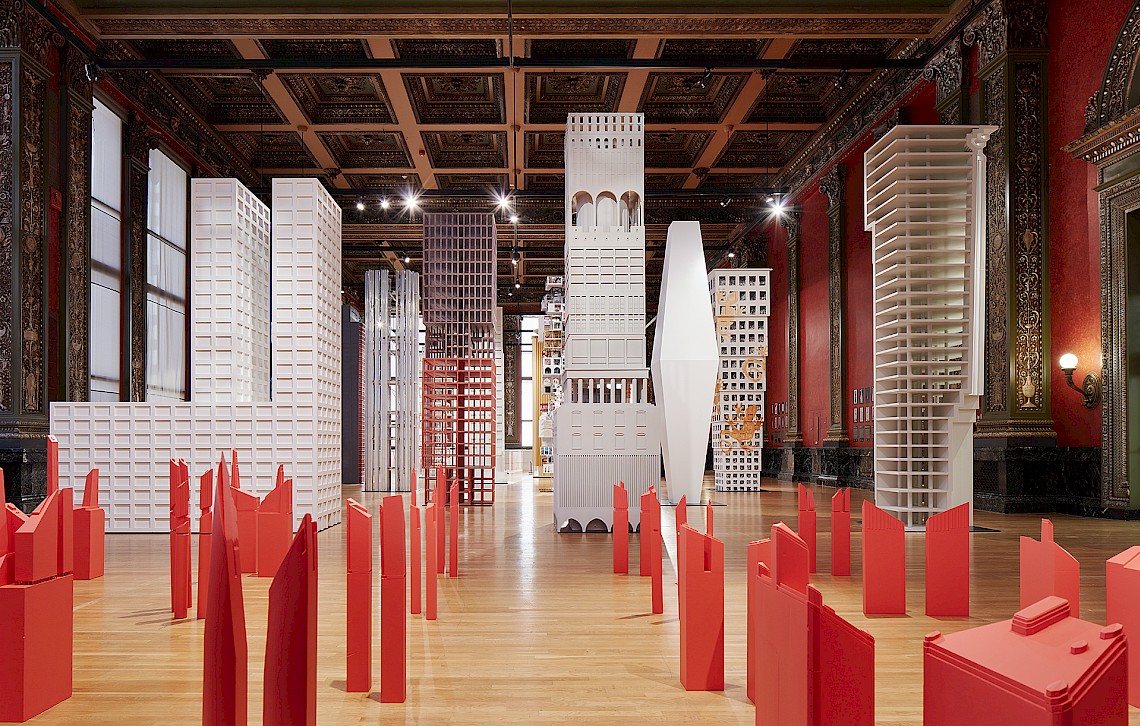

The 2017 Biennial in Chicago, entitled Make New History, follows in Stanley Tigerman’s footsteps by introducing a new generation of Tribune Towers that explore the competition’s complicated afterlife and connect the groundbreaking dreams of the past with the most pressing issues of today. Artistic Directors Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee have asked emerging practices from around the world to turn one of the Chicago Cultural Center’s grandest spaces into the “Vertical City” display: a lofty grid of imaginative towers representing a new generation of “late entries.”

Two rejected designs from 1922 serve as contrasting points of departure. One is Loos’ Doric column, which proved a touchstone for Postmodernists who looked to both metaphor and historical motifs for inspiration. The other is a never-submitted Modernist design by Ludwig Hilbersheimer, which only exists in the form of one perspective drawing – opening up questions about how architects reinterpret visions from the past in the absence of documentation.

The new towers are created by an international group of young architects: 6A Architects, Barbas Lopes, Christ & Gantenbein, Ensamble Studio, Eric Lapierre, Barozzi Veiga, Go Hasegawa, Kéré Architecture, Kuehn Malvezzi, MOS, OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen, PRODUCTORA, Sam Jacob Studio, Sergison Bates, Serie Architects, and Tatiana Bilbao.

Some designs take stylistic pastiche to new heights, while others question what Loos’ column would look like with different references and different materials. Many rethink what a skyscraper can do to accommodate new types of work and play in the twenty-first century, from the sharing economy to alternative ownership models. Digital collage, new forms of physical craft, adaptive reuse, historical anecdotes, innovative building technologies, and cultural critique are all vividly on display.

Taken together, the new models comment on the ways that ideas in architecture circulate between past and present as much as between architects themselves – and how exhibitions take on lives of their own as they make history for centuries to come.

Explore more of the Tribune Tower’s afterlife in the Are.na channel below. Or visit the Biennial's Are.na profile for more images, research, and information on this year's themes.