Dellekamp Arquitectos’s proposal for a linear pavilion in Chicago’s Garfield Park that inverts the idea as well as the form of a border wall may be one of the most politically resonant responses to “Make New History.” Rejecting the President’s vision for a closed border, the imagined architecture consists of an extended wooden portico whose lofty bays might hold the kind of cross-cultural dialogue made impossible by the ongoing militarization of the Southwestern landscape.

Dellekamp Arquitectos is a Mexican architecture studio of nearly 35 designers based in Mexico City. Founding principal Derek Dellekamp spoke with the CAB blog recently about engaging with “Make New History,” the idea for a pavilion that knits different nationalities together, and the freedom to speak one’s mind at a broad architecture exhibition.

Dellekamp Arquitectos have designed a series of public installations prior to this fall’s Biennial, including entries to the 2008 and 2016 Venice Biennales. With every pavilion, Dellekamp explains, “we always try to make it about something that we’re interested about, that we’re worried about, that we feel it is important to address.”

The Chicago Biennial and its overarching curatorial prompt “Make New History” was no exception. Dellekamp Arquitectos is known for dialing in the meticulous details of its domestic and commercial spaces—usually rectilinear compositions in concrete, glass and wood. So a commission from an international survey like the Chicago Biennial is a chance to take a reflective pause and “an opportunity to express what’s on our minds,” says Dellekamp.

The firm’s contribution is titled Wallderful, a play on Donald Trump’s overblown promises during the 2016 presidential campaign to build a border wall. “We started working on the project slightly after the election,” remembers Dellekamp, recalling Trump’s incessant claims that “Mexicans would pay for it, or ” that it would be “wonderful, beautiful, great.”

As a Mexican architecture studio with a keen interest in the Mexican-American relationship and contemporary politics, the firm felt compelled to address Trump’s divisive rhetoric and the nearly-religious fervor with which the idea of a wall resonated North of the border.

“We were very aware of the impact that this had, not only on the United States but also everywhere in the world, and especially in Mexico,” explained Dellekamp. “There is no doubt that whoever is president in the United States has a big impact in Mexico [and] impacts us on a daily basis.”

In the context of “Make New History,” Dellekamp saw the current conversation around the U.S.-Mexico border as a reverberation of historical forces that have marked the landscape of the Southwest for centuries—a pattern of exclusion that architects could no longer ignore. The Biennial presented an opportunity to take a political perspective on design discourse while proposing concrete solutions and valuable community infrastructure.

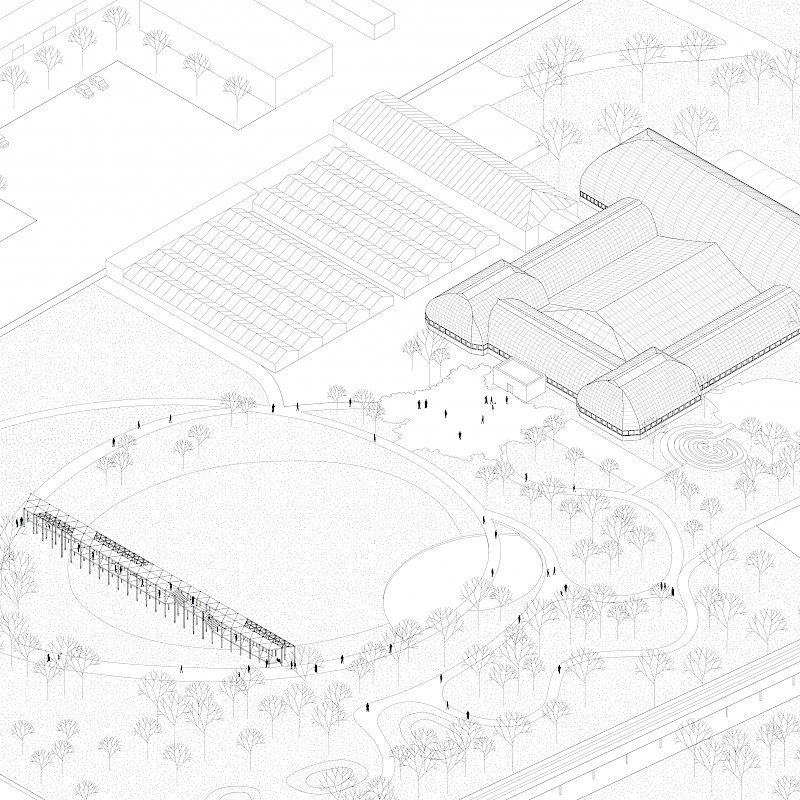

“We knew we wanted to make some sort of interactive, playful place to celebrate diversity, that could be used in several ways,” explains Dellekamp. These two prompts inspired the proposal for a portico, which evolved into a kind of anti-wall. While the structure is tall, solid and linear, Dellekamp calls the Wallderful pavilion “a nightmare wall for Trump” because it welcomes rather than excludes. The design is an airy structure meant to encourage gathering and celebrations under its long roof and among its many platforms—a place for people to come together and share their cultures.

Dellekamp has already tested versions of the same idea as tools for cultural exchange in public space. The architects developed its modular structure of triangular wooden platforms and beams for an annual city-wide architecture event in Mexico City. The latest version was realized as the House of Switzerland Pavilion, built to celebrate seventy years of diplomatic relations between Switzerland and Mexico.

The flexible system helped the Casa de Suiza pavilion transform its shape over time to to accommodate lectures, parties, food vendors, leisure, and shade.

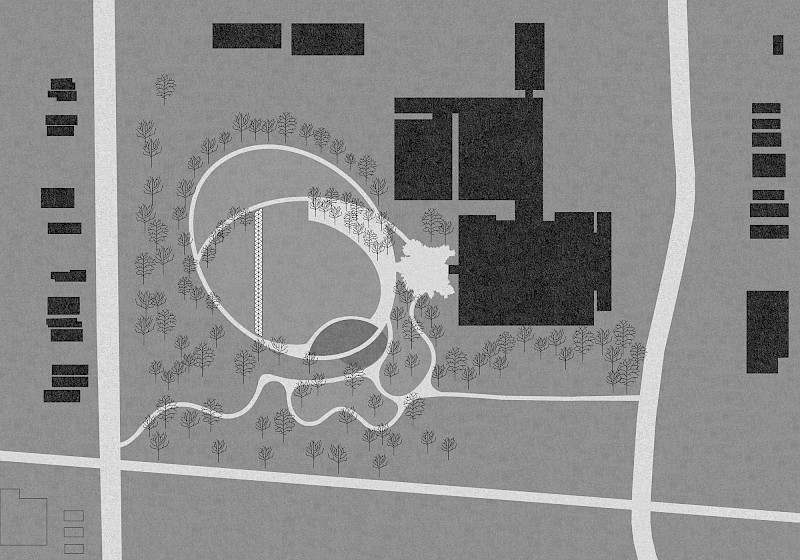

Dellekamp Arquitectos recalibrated the structure for the Biennial as a site-specific proposal for Chicago’s Garfield Park, a historic green space in the heart of the culturally diverse neighborhood of the same name. The proposed structure would offer a spatial counterpoint to the renowned Garfield Park Conservatory, opening itself up to the landscape in contrast to the Conservatory’s domed greenhouses.

“What had us very excited about Garfield Park,” said Dellekamp, “was not only how beautiful the place is, but also how complex the community in that area can be, and the important role that Garfield Park can have as a high quality public space for this community.”

In a city as deeply segregated as Chicago, Dellekamp highlighted Garfield Park’s historical significance as a haven for the city’s large Latino and African American communities.

“We thought it was really fun to create this wall which does exactly the contrary of dividing,” states Dellekamp, “and instead brings all of these cultures together,” said Dellekamp, who visited the area and discussed the idea with locals last year. “We talked about their desires for a pavilion there and ways to interpret the dynamics of Garfield Park throughout the seasons.”

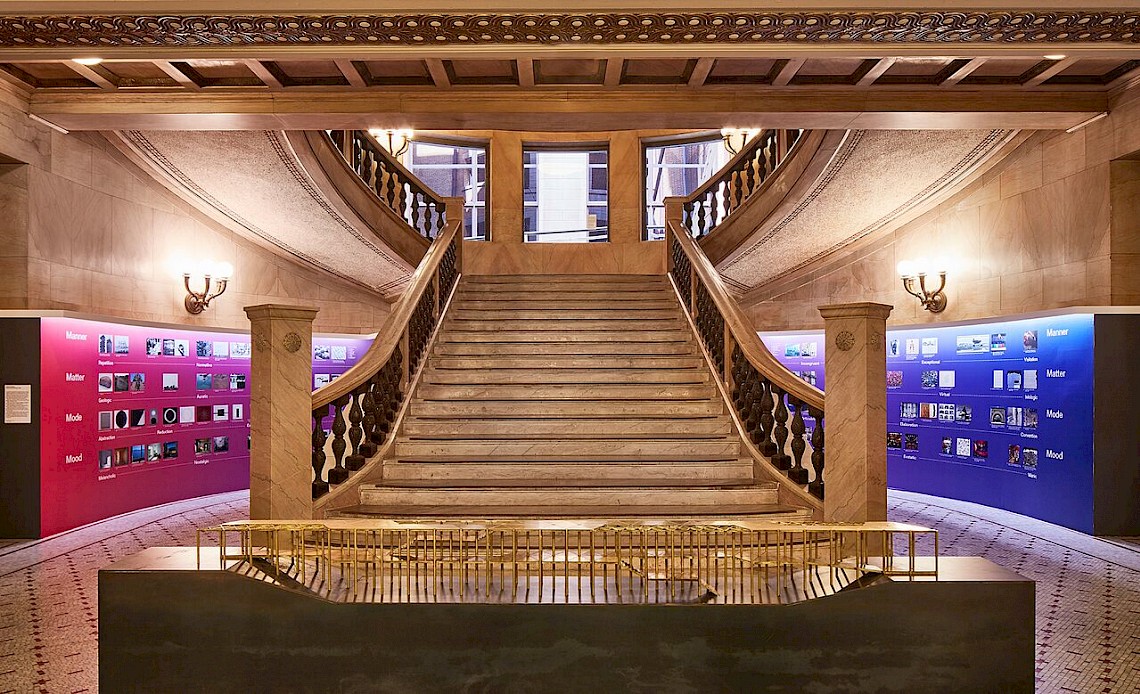

Wallderful is represented at the Chicago Cultural Center by a dramatic cast-bronze model in the building’s Randolph Square lobby. Nearby is another modular, geometric environment designed by Frida Escobedo, who is also part of a rising generation of young Mexican architects. Theirs may be just one of nearly 150 works at the Biennial, but Dellekamp Arquitectos’ commitment to social inclusion, political critique, and formal detail represents a concrete model for building community in architecture while turning history’s inequities on their head.

Explore more architectural responses to the border wall in the Chicago Architecture Biennial's Are.na channel below. Check out more content or add your own by visiting the Biennial's profile.