Detroit, the city that once epitomized American industry and wealth, is now the site where architects are working most intensively to reimagine and regenerate the post-industrial urban landscape. The creative population of Detroit and surrounding Michigan has taken this challenge to heart, endeavoring to use design as a means to serve the city’s long-standing communities with new energy and purpose. It is particularly at the nearby University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning that innovative architectural thinking has translated into ideas for preserving the city’s social fabric while demonstrating its potential to become a center for experimentation and creativity.

In 2016, the U.S. Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, curated by architecture editor and critic Cynthia Davidson and Venezuelan architect Monica Ponce de Leon – who served as Dean of Taubman College before becoming Dean of the Princeton University School of Architecture in 2015 – focused specifically on the revival of the post-industrial American city through speculative proposals for Detroit. Entitled “The Architectural Imagination,” the exhibit focused on reversing radical changes to Detroit's urban fabric as the city continues to navigate the fallout of economic crisis, bankruptcy, and population loss. The commission process for the Pavilion’s twelve proposals began in 2014, with a meeting between the participating architects and an advisory board at Taubman, and extensive groundwork throughout the city.

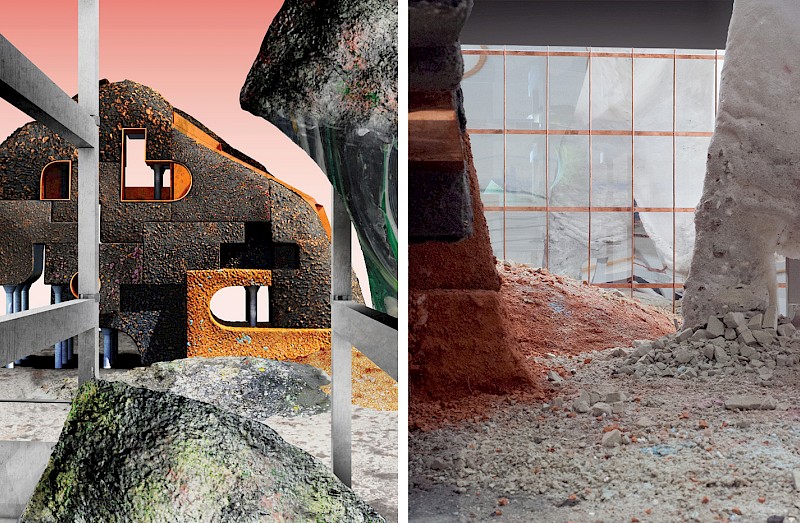

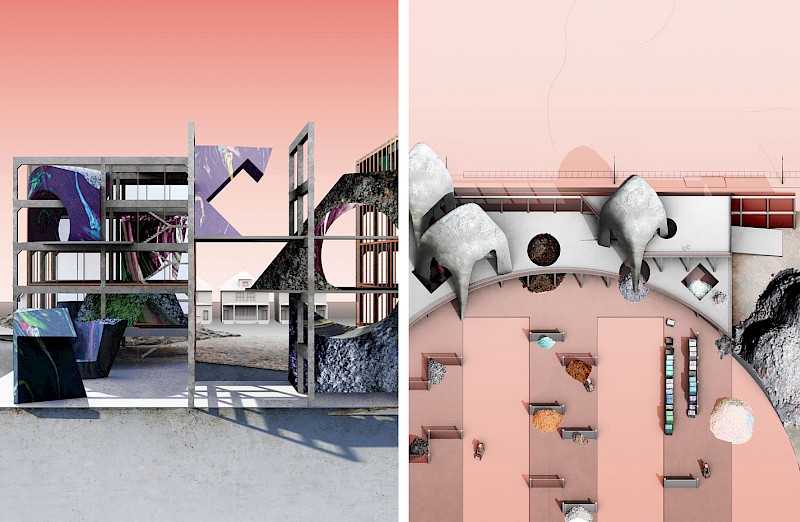

T+E+A+M, a collective formed by Taubman faculty members Thom Moran, Ellie Abrons, Adam Fure, and Meredith Miller, was among the studios invited to participate. The group chose to reimagine the historic Packard Plant, the vacant, but iconic, factory which has been a symbol of the city’s rising and falling fortunes. Resisting the building’s status as a popular subject of “ruin porn,” the design makes the structure functional once again — as a reserve of concrete, brick, and other materials that might be used for new construction. Entitled the Detroit Reassembly Plant, the project selectively demolishes debilitated portions of the plant, “combining the rubble with plastics and other post-consumer materials recovered from Detroit's waste streams” to build new structures within. The resulting building is comprised of “zones for material sorting and processing, production areas for building construction, a research and development park dedicated to advanced building technologies, public demonstration areas, exhibition galleries, and public outdoor spaces.”

Ghostbox, the practice’s contribution to this year’s Chicago Biennial, takes a similar approach to a different abandoned building type: the exurban “big box” store. Here, the building’s matter is partly demolished and reassembled to create inhabitable spaces at different scales throughout the expansive volume of the former business. “The aim is not a wholesale transformation of what was there, nor a romanticization of the building’s history,” writes T+E+A+M in the description text that accompanies the sizable model on view at the Biennial. Instead, the project presents a way to engage with disused properties in situ as a setting for new happenings. Much like SITE’s deconstructed BEST Products stores from the 1970s, T+E+A+M’s design challenges a whole set of social assumptions around this familiar and quintessentially American building type.

Where ruin porn romanticizes the abandonment of infrastructure, T+E+A+M approaches it as raw material, available for “reassembly,” waiting to be shaped into places that can be inhabited and used productively again by many different communities. Imagined not only as speculative proposals, T+E+A+M’s projects are presented as grounded design solutions for the fabric of Detroit and the broader, post-industrial American landscape. Their work celebrates Michigan’s legacy as the center of U.S. manufacturing and encourages viewers to consider architecture on a longer timeline, proposing a sustainable, future redistribution of materials left behind throughout past eras.

We asked T+E+A+M a few questions about Ghostbox and the practice’s identity within the landscape of emerging architecture firms.

CAB Blog: The four members of T+E+A+M came together to work on a project for the 2016 Venice Bienniale - before that, I wonder how you realized your interests overlapped so well. Were there particular sites - maybe other than the Packard Plant - or previous individual research work, that inspired you to address alternative processes to employ the material abundance of Detroit?

T+E+A+M: We’ve known each other since we each arrived in Michigan in 2009. Even though we originally started independent practices that pursued different interests, we’ve been involved in periodic collaborations with each other and other friends and colleagues over the years. Originally, we were part of a collaboration called Five Fellows, where we pooled our fellowship funding to buy a vacant house in Detroit and each designed and built an intervention in the house. It was a naive project in many ways, but one that helped us better understand the complexity of Detroit’s economic, cultural, and material conditions. At the time, the project also helped solidify our independent design ambitions that we continued to chase down through our individual research and practice. Looking back, we certainly learned from the experience of coming together around a shared project and we’ve been working on materiality and image for a long time.

CAB Blog: Throughout your practice's discourse, there is a repeated concern with the visual mediation of ruins, and yet you are producing very beautiful visuals of those ruins as well, though reinvented as practical spaces for the future, of course. How do you internally address the aesthetic of your visuals? Are there specific angles you try to avoid, or embrace?

T+E+A+M: A frequent response to our work is an internal conflict between being drawn in by the dreamy aesthetics and being put off by a state of matter that is entropic, or in transition, or decaying. Gradient mountain ranges coincide with piles of building rubble; monumental spaces emerge from roughly excavated slabs under a corrugated metal roof. There is a visual and spatial pleasure to the experience despite its unstable material reality. To us, the irreconcilable commingling of these qualities (pleasure/decay; resource/waste; optimism/ruination) is intrinsic to contemporary environments and cities. We hope to avoid “ruin porn,” which we see as a romanticization of the grave effects of economic hardship. Instead, we believe architecture has the capacity to reshape our perceptions of building debris or disused structures, and the values we assign to them. We also steer clear of nostalgia. T+E+A+M’s work looks squarely at the present.

CAB Blog: This is now T+E+A+M's second Biennial and it's interesting to think about these types of survey exhibitions as entry points for new practices that can set the ground for their "critical discourse" prior to building projects. How do you think about this relationship, and the way that audiences of these exhibitions can support your work to grow further?

T+E+A+M: Participating in the Chicago Biennial has been such a valuable experience for T+E+A+M, not just in terms of exhibiting our work to a large audience, but also in terms of the internal discussions and design process we had while developing Ghostbox. We want our ideas to connect with a large audience, but we also want to use the exhibition’s format as an opportunity to work out ideas about building, since building is an important goal for us. Big models seem to be our answer to this dilemma; a model is immediate and accessible to people with or without extensive knowledge about architecture. And at the same time, building a model at a large scale introduces questions of materiality, interior, tectonics, scenography. A model can be a test bed for design issues at the building scale.

CAB Blog: In the wall text for Ghostbox, you situate your work outside of renovation, adaptive reuse, preservation or restoration. Instead you refer to it as "redistribution," which pertains directly to the of materials and resources themselves. Can you elaborate a little on this decision, and discuss why the project could not be seen as any of those other architecture processes? Does the proposal invite for constant change over time rather than a more static building form?

T+E+A+M: We like “reassembly” because it avoids the nostalgia of preservation and restoration and embraces radical re-imagining in a way that renovation and reuse can’t. Reassembly is a term we began using for our first project, Detroit Reassembly Plant. Reassembly is a strategy for conferring value to building components, waste materials, or other objects that have shed their prior use value. For us, this involves both literally reconfiguring these materials in space and realigning these materials with an alternate image. For the Detroit Reassembly Plant, this meant recombining physical fragments of the building (brick and concrete rubble) to produce a new aggregate material while also transforming the perception of these materials from ruin to resource. The image of the architecture is instrumental. For Ghostbox, the idea of reassembly opens up new conceptions of the empty big box store that extend beyond more familiar forms of reuse that simply fill the container with new program. Through partial demolition, disassembly, new construction, and reassembly we take advantage of the material reality of the existing site without being limited by what came before.

CAB Blog: In Ghostbox, you look at the big-box superstore as a typology that is being "increasingly abandoned as contemporary habits transform with online shopping." Do you think that the proposal for the Packard Plant is specific to Detroit or can ultimately be applied to nationwide sites that match this type?

T+E+A+M: Ghostbox addresses vacancy in first-ring suburbs, while we designed the Detroit Reassembly Plant as a radical reimagining of the iconic Packard Plant. However, we see the strategy of reassembly as applicable to other vacant, post-industrial sites like the Packard Plant. Detroit may be unique in its large share of these sites, but it’s certainly not alone in contending with the spatial effects of radically shifting economies and demographics. So in this sense, the Detroit Reassembly project is prototypical. However, how this strategy plays out from place to place really depends on what a given site affords, in terms of raw material but also its cultural representation.

Explore more examples of material reuse in contemporary architecture by clicking into the Are.na channel below: