Ângela Ferreira’s Zip Zap and Zumbi at the DePaul Art Museum for the Chicago Architecture Biennial continues her long practice of her using quasi-architectural models as installation art. Ferreira presents research on a site or project, which usually include photographs, sound recordings, film clips, and performance. All of these make clear the orientation one is to adopt with regards to the site: post- or de-colonial. This is particularly important in the context of the Chicago Architecture Biennial, given the risk for design and architectural exhibitions to slip into historical amnesia in the name of progress or innovation. What is most compelling about Zip Zap and Zumbi is the insertion of slavery into the discussion about modern architecture, especially at this moment when the history of slavery and the status of its representation in public monuments are under fierce debate across the United States (epitomized by the events in Charlottesville, VA) and in South Africa (#RhodesMustFall).

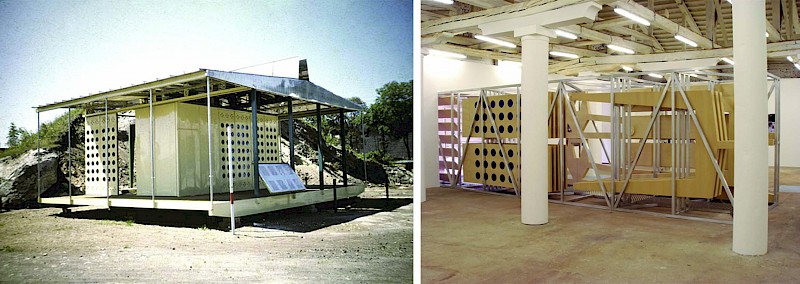

Zip Zap Circus School (2000-2017) takes as its material two “unrealized” architectural projects: Pancho Guedes’ Zip Zap Circus School in Cape Town (1994) and Mies van der Rohe’s 1912 model for a portable at the Kröller Museum in Amsterdam. The bookends of early- and post-modernist architecture are combined into one work that documents, celebrates, and also critiques the notion of architecture as social reform (Zip Zap Circus School was designed to create educational opportunity and vocations for Cape Town youth). Implicit in the combination of references and the structure itself is portability, a concept I will come back to. But as with others of Ferreira’s architectural installations, their provisional status contains a conceptual slippage from “unfinished” into the weightier “unrealized”: prototypes stand in for historical contingency and the failures of modernism.

Yet Zip Zap Circus School is not a proposition about architecture as such. Ferreira’s prototypes use architectural shorthand, but the gallery environment is what registers the installations as both didactic and allegorical, if secondarily immersive and/or performative. This orientation to installation art was perhaps best seen in Ferreira’s Maison Tropicale installation at the 2007 Venice Biennale and its accompanying documentary made with Manthia Diawara [1]. Zip Zap and Zumbi mixes modes of architecture and includes supplemental material, all in the service of the comparison: an essay-like thesis that a fraught mobility is the underlying condition of globalism.

The space of art is necessary to consider mobility as such, and particularly how Africa has acted as a signifier for remoteness throughout the history of modern art and architecture. Africa (I use this generically) provided the testing grounds, a limit case, for those committed to idea that the built environment could act as social engineering. Modernist artists and architects were, on the whole, ecstatic about their opportunities to transgress cultural and geographical boundaries, but were often met by the reality of (im)mobility. Ferreira’s works do not simply reconstruct or mimic the models and prototypes of modernism, but most often they are truncated or presented as suspended form. Her work suggests an incompleteness of the modernist project—modernism unrealized—but also gestures to the unwillingness of the site to receive such overtures.

Ferreira has consistently shown the relationship of the sender and the receiver in architectural globalism. A striking photo in the documentation for Maison Tropicale (2007) shows foundation slabs where Jean Prouvé’s portable homes were once built in Brazzaville and later abruptly removed. These are the micro stories that Ferreira’s work tells, the mundane and literal imbalances of power in what is romanticized in architectural theory. Moreover, she has brought out a relatively little known history of modernist architecture in the former Portuguese colonies, which are often overlooked. The Lusophone world fills out the story of colonialism and connects it more explicitly to the transatlantic slave trade. Architecture played a key role in registering the departures and returns of people from their homelands, as in the Brazilian architecture of Lagos, Nigeria created by freed Yoruba slaves, which is evoked in Zip Zap and Zumbi. Additionally, her interventions have highlighted the relationship between colonial modernism and the socialist modernism that post-independence Mozambique attempted. [2]

As Paul Gilroy argues in The Black Atlantic (1993), modernism begins with the slave trade (it is “capitalism with its clothes off”). [3] Wattle and Daub (2016) is Ferreira’s clearest statement yet about the relationship between the two institutions of slavery and architecture, and fitting for her interest in modernism. The work includes a built structure made using the wattle and daub technique, which holds a slide projector throwing an image onto the wall of a slave market in Portugal. The installation is accompanied by Brazilian musician Jorge Ben Jor’s “Zumbi” (1974). If one follows the references (which in this case only takes looking at the wall label), the connection between the wattle and daub technique and slavery consists of larger issues of erasure and ephemerality that strike at the modernist fantasy of permanence and stability. Moreover, the wattle and daub technique reminds us what remains after various social engineering projects fail to be exported.

Ferreira’s installation art activates a slippage between historical specificity and allegory. Exhibitions like the Chicago Architecture Biennial rely on installation art to do the allegorical work that models, proposals, or even historical displays cannot do. The variety of images (both sonic and visual) in Zip Zap and Zumbi straddle space and time, new construction and historical documentation. Intermediality, a foundational aspect of installation art, works on at least two levels in requiring a connecting of the dots of specific historical references to slavery and architectonic space, which then open out to the institutions of slavery and architecture generally. In other words, the perceptual action of connecting built structure, projected image, and music condition us to engage in the “from this to that” of allegory.

Ferreira’s work plays on the relationship between the literal and its buried meanings, which exemplifies the relationship between the global north and south; James Clifford has long argued that all ethnographic texts are already allegorical. The initial impetus of ethnography was the desire to find elsewhere the European self and to test whether Western humanism could hold up within the colonial setting, which was unmistakably inhuman. If European modernism took as its challenge extreme acts of displacement, othering, and empathy, Wattle and Daub might indicate the danger of the universalizing impulse in allegory and confront it with its death drive. On the other hand, the work gestures to the utopianism described in Gilroy’s Black Atlantic with its reference to Ben Jor’s “Zumbi,” a song that celebrates resistance to capitalism through folk and collective knowledge. Engaging Jean-Luc Godard, Jean Rouch, Jorge Ben Jor, Jean Prouvé, and Paulus Guedes, Ferreira presents figures not easily caricatured in their ethnographical humanitarian work. These figures are also foundational in the history of the avant-garde and its embrace of intermediality, despite its detractors.

The question of whether Zip Zap and Zumbi is meant to structure an aesthetic experience for the viewer or simply to instruct her on the history of colonialism is not unique to Ferreira’s work; it is central to global contemporary art. With various activations of the gallery space possible, the work can perhaps be enhanced with a communal experience of a performance. At base, however, Ferreira’s work has connected histories and structures in a careful presentation of the lesser-known sites of modernism.

-

Manthia Diawara , director. Maison Tropicale. 2008 . Republic of Congo/France . French, Portuguese , Wolof with English subtitles. 58 minutes. Third World Newsreel.

-

See Ângela Ferreira’s Study for monuments to Jean Rouch’s Super-8 film workshop in Mozambique (no 2) (2011) documented in Mark Nash, ed., Red Africa: Affective Communities and the Cold War (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2016), 86-90.

-

Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 15.

- James Clifford, “On Ethnographic Allegory” in Writing Culture, eds. James Clifford & George E Marcus (Berkley: University of California Press), 98-121.

Delinda Collier is Associate Professor of Art History, Theory and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is currently researching the history of new media and old media in art production in Africa.

Ângela Ferreira: Zip Zap and Zumbi is now on view through December 10, 2017 at the DePaul Museum of Art, a Community Anchor Site of the Chicago Architecture Biennial. The exhibition is organized by DPAM Director and Chief Curator Julie Rodrigues Widholm.

Learn more about the exhibition and how to visit DPAM here. For an overview of how to explore the Biennial's exhibitions and programs, click here.